INTERVIEW WITH MELITTE BUCHMAN -

7 February 2013

Joe and I got the privilege of meeting with Melitte Buchman at NYU's Fales Library to speak about her part in the show, scanning some of the original posters and restoring them to look new. In addition to learning some of the more technical aspects of her work and the process, we spoke about larger concerns of digital restoration versus digital preservation, copyright and Cesare Brandi's treatise on restoration, which plays a large role in definition how archivists and historians operate today within their fields.

Here are a few sections from our conversation:

Could you give a general description of how you got involved in the process, who contacted you specifically - was it Edward or Hugh, or was it Michael Cohan?

It came to me through Edward Holland. He and I went to grad

school together. He's a panoramic

photographer, and he's with our staff here. They needed some high-res pictures

for the exhibit that they were putting out. So, I went over to them at the

gallery, and I said thank you for showing me the archival material. They were

too fragile to be through a scanner.

Anyway, I'm the digital content manager here, so it would've come

to me one way or the other. It's just came through a personal route. So when

people need things digitized for preservation, they talk to me because I'm part

of the preservation department and part of the Digital Library.

And how long have you worked here?

Nine years. Do you know

what a digital library is? Digital

libraries were initially invented because it was felt that students didn't want

to go to physical buildings anymore, that they wanted to go to the web and you

had to sort the truth out on the web as opposed to ‑‑ I can do this in

Photoshop and then make it look really neat. If you go through a trusted

portal, which NYU is, and you look one of our projects like this one,

you're going to see the truth of the object.

I think what we're actually talking about is what Cesare Brandi talked

about - the authenticity of the original artifact. Do you know Cesare

Brandi? It’s totally worth reading his stuff. It's about 45 pages. I don't

remember what it was from, but it was pretty revolutionary at the time. He was

talking about paintings and historical artifacts. The entire course of

preservation and restoration changed course with that treatise that he wrote

because he was talking about not making things nice, not putting the aesthetic of the present or the

materials of the present into ancient artifacts; so, the idea is that it's a

painting and everything has to be reversible. If it's something that needs to

be stabilized, then you need to respect the historical nature of the thing.

He's really the grandfather of that idea. I was saying that in digital

libraries we take that very seriously, so if we see something that's ripped and

dirty and all of that stuff, we don't try to make it better. We try sort of

this weird exercise where we're using really expensive high‑end equipment where

we could fix these things, but we know it's the wrong thing to do. When you see

a picture that we've made here, it looks within 1 or 2 percent, like the

original artifact, except for the fact that it's completely denatured. It's no

longer in the physical world. For example, part of the reason that we

photograph all of the physical pages with black around them, black surround, is

so you can see that it's a physical page. I find that's the biggest part of my

job is worrying about what is the end‑user going to need to know about the

context of this object to render it mentally correctly.

The thing with Gran Fury was that the posters were how old -

twenty years? And colors had shifted.

There was staining. There were broken edges. There were fingerprints. There

were all kinds of things, and I was about to do what I always do, which is

preserve exactly the look and feel of the historical nature of the thing. And

then I said, “This is what I am doing. Is this what is wanted.” They said, “No,

this isn’t what's wanted. What's really wanted is the way it looked back then.”

So, you get to go into Photoshop and change the white point and clean up the paper. Our equipment is really high end here, so the

result looked great. It looked new. It was huge, and we got rid of the moiré,

which is intrinsic to the printing.

(Referencing her computer screen) Here, this is the perfect

example. It's this kind of thing where if you're photographing something,

especially from a newspaper that has a core screen of about 80 or 85, that when

you digitize it at 300, 400, or 600, it adds this other patterning on top of it

that's not intrinsic to the original. There's a bunch of digital tricks that

you employ to get rid of it, so I did some of that with the Gran Fury things,

too. I don't know if you saw the installation, but it really looks

spectacular.

Yeah, that's what really inspired me to do this because it was

beautifully done.

My problem is it's the wrong thing to do. The only reason I did

it is because curatorial always stands on top of the service provider. I'm the

service provider but the gentlemen that I met ‑‑ it was only with their

approval that I would take this other approach. And part of that is sort of a

philosophical, anti‑colonial thing, like who are we to make decisions about

what your content is?

I have an example that may be helpful of this where we have in our

archives a collection called the Abraham Lincoln Brigade photos. The Abraham Lincoln Brigade was part of the Spaniard

Civil War era; communists go over to fight against Franco Luce, but they have a

core of photographers. Two-thirds of their negatives came to us and one‑third

went to Moscow. The two‑thirds that are ours are what photographers call “bulletproof”.

They're super, super dense, which really blows out the value. So it sort of

looks like a snowman in the snow. They look very high contrast and very light.

When I saw the collection, I knew that it was going to be a problem. We [had]

the negatives to process out, but the photographer was still alive, and his

name was Harry Randall. I did an interview, and I said, “You know, when you

were photographing this, how did you see this collection?” He said, “Oh,

they're supposed to look like a good, snappy black‑and‑white that you would see

in a newspaper.” I said, “That's not what they are. They're bulletproof negatives that are very

high contrast.” He said, “You know, we never knew where our chemistry was

coming from. We would be developing a stream in the middle of the night, trying

to avoid dying. What we did was we overdeveloped everything with the hope of

getting anything,” which means, first of all, he's an amateur photographer.

That's not how you handle that. But second of all, it allowed me the

flexibility of being able to say since he is the creator and he is telling me

what he thinks this thing can look like ‑ should look like - then I can take my

digital tools and make it so. I didn't make it so in the master file. I made it

so in the file that we called the derivative making file. So, the master file

actually is a 16‑bit negative of an incredibly low contrast. But the D file, which is what you would see

small JPEGs minted from on the web, looks as close as I could get to a good,

snappy black and white because that's what he had asked me for. That's how he

had defined the collection himself.

So normally I would never, ever do this. I want to make this

really clear - it's bad archival practice to go in there mucking about and

making decisions about bettering something; it was only because the curator

said, “I am Gran Fury, and this is the way I see it” that it let me do that. One

should never be doing that normally.

You provide an answer that I was partially expecting. But, for

example, I spoke with two Gran Fury members, and they each had a different

attitude toward it. Originally as a collective, they had said, you know, “The

art isn't the point. The posters aren't the point. They're not meant to last. It's the message

that's the point.”

Okay, you have to read Cesare Brandi now because what the

collective is doing, they’re making a new object. They’re not making the same

object. In other words, if somebody else did that, it would be infringing on

copyright. Because they have their own copyright, they may do it because it's

their intellectual property. But Cesare Brandi also talks about the fact that

if you are doing a restoration or preservation, you can never have the artist

involved because the artist will always remake the object.

Gran Fury, from my point of view, sees their pieces as content,

and if they're not content, they are content and container. And with content

and container, they have sort of a unique balance. Here we call that kind of

thing “essence and wrapper” - you have the essential message, but it’s mitigated

by what the wrapper is. So, if you see a letter written by George Washington

and the paper is faded, that tells you a great deal not only about the content,

but about all these other sort of characteristics. The object is old, you know.

It's been around a long time. It should be venerated, whereas if it's on a

pristine white sheet of paper, it's no longer the thing, itself. I think people

who are creators or artists tend not to see that, and people who are archivists

and historians tend to see that.

***

You can't talk about digital without talking about copyright, and

we are not able to serve up many things after 1924 because of the copyright

legislation that was passed. You know the story: Ronald Reagan was president,

Mickey Mouse was about to fall out of copyright, and Disney wooed Congress in this

huge, gross political move.

Copyright went from something that was meant to protect the

creators so that they could gain some income from it. And it became something

that corporatized the assets, themselves. And the irony, of course, is that

nobody cared that much about Mickey Mouse, but it forever changed the landscape

of copyright. So that, for us, is always the painful thing. Do we put this

material out here in spite of the fact that we might get sued or we will have a

cease and desist sent to us or don’t we? We've had to set up very distinct user

classes about where these digital files can be seen.

Right. So, to rehash, digitization does change the nature of

the object. Copyright plays a humongous issue.

Putting [archival materials] on the web is seen as publishing,

so it falls under publishing laws, as well. There are always generational

issues in the past. If you had a book and you wanted to save it in

microfilm ‑‑ Microfilm is less desirable than the original book. The thing with the digital copy is if you

make a copy of a digital copy, it's exactly the same as the digital copy; so,

the potential goodness of the file can be exactly the same as the original. And for some reason that has turned against

us in a bad way, when we had hoped it would be liberating. I think in some ways

it is liberating because you can now go to the web and look at, you know ‑‑

Digital Scriptorium will show you the most valuable manuscripts held in this

country, which you never would have been able to see except by getting a pass

from NYPL and gloves and all that. So there's some very good things about being

able to digitize.

***

Going back to earlier in our conversation, I love that term you

use[d], ‘denaturing’. I really like that. I think that gets to the heart of

it.

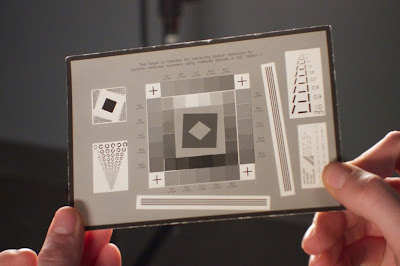

It's kind of a weird Zen exercise in a way. There are a lot of

digital tools that are made specifically to enhance and make things look

better. We actually have to turn all of those tools off. We calibrate our

equipment so that what you see is what you get. That's hard. All of our

scanners we have to use the photo spectrometer made by X‑Rite. And what we have to do is we have to

calibrate and characterize so that what you see is actually what was

there. It doesn't make it brighter. It doesn't

make it redder. It doesn't make it bluer. The photo spectrometer that we use,

which is a good one, is an expensive device, and you have to be trained on

it. So, you know, we use sort of a moderate

level of spectrometer, which is about $3,000, but people like L.L. Bean, who don't

want to get 10,000 shirt returns because it wasn't exactly that color

blue, use the really high‑end. You could pay millions of dollars. They're not

making any of the stuff for us. We're sort of backing on to ‑‑ We're

appropriating other people's technologies to manage our own.

In my defense, I really enjoyed changing the poster to make it

look cool, and I really enjoyed using my digital skills to make it look big and

sharp and detailed, but it's a bit of a fabrication.

Thanks to Melitte and the Fales Library staff for being so accommodating.

*Photos courtesy of Joe Mondello; portrait of Cesare Brandi via Cesare Brandi official website.

No comments:

Post a Comment