Creating and Re-creating AIDS Activist Art: The Biography of the Gran Fury Poster

"Someday...there'll be people alive on this earth -- gay people and straight people, men and women, black and white, who will hear the story that once there was a terrible disease in this country and all over the world, and that a brave group of people stood up and fought and, in some cases, gave their lives, so that other people might live and be free." - Vito Russo, "Why We Fight", 1988

Saturday, June 1, 2013

Monday, April 22, 2013

Interview with Robert Vazquez Pacheco

INTERVIEW WITH ROBERT VAZQUEZ PACHECO AND JOE MONDELLO -

19 JANUARY 2013

Joe and I got the opportunity to sit down with Robert Vazquez Pacheco, a member of Gran Fury who had the unique distinction of not being an active artist in the collective; however, his influence is greatly apparent in the work - he's even featured in Kissing Doesn't Kill! Robert shared with us his experiences at the time and how his professional work and heritage aided Gran Fury in disseminating information.

Could you tell me

first about your training?

I actually have no artistic training. One of the interesting

things about Gran Fury is that not all of us are artists. One was actually a nurse – a registered

nurse.

Really, who was that?

Michael Nesline, and Richard Elovich was a writer. The

artists were Marlene, Donald, Avram, Mark and Tom, who is a filmmaker. Michael

and I were the non-artistic ones.

Can you talk a little

bit about your role in the collective and how you got started?

Well, a friend of mine whose name was Deb Levine was working

at Creative Time here in New York – I think this was in 1988 - and Creative

Time had given them money to do an installation. So, Deb asked me if I would be

willing to help come up with an installation concept and help to install it.

ACT UP was approached to do it by the museum, El Museo del

Barrio and we were given a corridor. So, given that I was probably one of three

Latinos in ACT UP, it fell to me. So we

did condom instructions – how to put on a condom. We blew them up into very

large size wall posters and plastered the entire corridor with them. Then, there was something like a 16th

century Spanish baptismal font that was sitting in the middle of the space that

we would fill with condoms that the museum would empty regularly. Then we would come back in time and fill it

up again. (Laughs)

Oh, that’s great!

So after that, we were invited to talk in Columbus,

Ohio. I was invited to talk, along with

Gran Fury, at a show about AIDS. Tom and

I were on the same panel, and at one point I said something along the lines of,

“Well you know, I’m not sure who all the members of Gran Fury are, but I have

no doubt in my mind there are probably no people of color in the collective.” When

we came back to New York that Monday after the meeting, Tom called me and said,

“Do you want to be a member of Gran Fury?”

So that’s how I became involved - I opened my mouth, and this is what I

got.

(laughs) Are you

happy you did?

I am, actually. Michael and I are actually the only folks

that were actually working in AIDS at that time. So we were, for example, supplying a lot of

AIDS information. At that time, I was

the Director of Education at the Minority Task Force on AIDS - so we were able

to sort of bring information in and give context to it.

Absolutely – you were

the information resource.

Yes, for the group.

That’s the way that we worked, everyone had a certain set of skills. For

example, Marlene McCarty and Don Moffett were graphic artists, and they had

their own design studio called Bureau. So they would do the mock-ups for all

the pieces - I don’t know if you know about the old school stuff. They did the

electro-set letters and all of that because they were the ones that were

trained to do so. The rest of us did research,

and then we would sit down and discuss whatever the concept was, whatever the

piece was that we wanted to do. We would thrash it out.

Avram said we always had a lot of arguments, but I don’t

remember a lot of arguments, actually. I

think for such a group of strong-willed people who are very opinionated, we

actually could get work done without coming to blows, which is amazing.

For me, part of my role was to bring in perspective when we

were talking about representation, especially when talking about communities of

color. I remember a conversation we had about one of our posters, Women Don’t Get AIDS. It’s all white

beauty queens, and when I looked at it, I said, “You know, I hate to tell you

this, but I don’t think an African American Woman or Latina looking at this is

immediately going to identify with a white beauty queen.” You know? I mean, they will read the text,

but the image will not resonate for them.

So I did things like that with the group, and we had

conversions. Not so anymore, but we were

very reclusive. We had decided that what

was most important was the work. We didn’t want to do anything publicly to

be recognized. There were two things we didn’t want to happen that usually

occurs in the traditional art world: One,

we did not want to create art objects, so all of our stuff was ephemeral. They were posters, billboards – once they

were up, they got torn down and thrown away. That was purposeful on our part

because we never wanted to see a Gran Fury piece at auction 25 years later at

Sotheby’s.

We also decided that it wasn’t about individual members and our

identities. So when we did interviews,

the very few that we did, we never allowed photographs and would speak as a

single voice. No one would be identified.

It wasn’t about us. The most

important part was the work, for all of us.

Yes.

One of the funniest things that happened though, in talking

about personality issues, was a meeting we had with the collective, The Gorilla

Girls. We were talking about collaborating. I forgot where we were meeting, but

three Gorilla Girl members came wearing the gorilla masks to sit down with

us. And we were like, really? Nobody knows us and now you have seen our

faces and you can identify us. What the

hell, you know?! (laughs) Finally, they took off their masks because it was too

hot to sit in that room and try to communicate wearing a gorilla mask. It was really funny.

I bet it was a bit

distracting.

We thought that we were doing the “Garbo thing,” but

they went much further than we were. So as I said, part of my role was to give

feedback and look at work. Also, I was

the only member of Gran Fury, really, who didn’t mind speaking in public. So we would be invited to speak in a variety

of settings sometimes, and the rest of collective didn’t want to do it, so it

fell to me. We had a slide show of our work that I used when people would ask

for presentations. So, in some ways, I was the public face of Gran

Fury. I wanted that because again, I was

the only of person of color in Gran Fury, and it was important for the world to

know that it wasn’t just all male, white guys doing all the work; and Marlene

was invisible sometimes, as well. It

fell to me to sort of let everyone know who was there and who was doing what.

You mentioned that the

posters for the collective, as a whole, were ephemeral; they weren't meant to

be precious objects. However, they

really came to be seen as the face of ACT UP.

What is your attitude towards that?

I would say that we were the most successful of the groups

that were making visual work in ACT UP. When

you went to an ACT UP demonstration, you didn't only see a Gran Fury

poster. ACT UP was very democratic in

that way. There were a lot of different

people who would make posters that showed up.

AIDS Demographics by Douglas Crimp is a great resource to show

you how many people were doing this. For

us, what we realized was because of our connections, especially in the art

world, and because of the particular time, we were able to use the art world.

Yes.

All of projects were funded by the art world, by museums,

foundations, public welfare foundations, Creative Time. We used those connections

to be able to do that. I feel as if we

were one of many. I think that all of us

would say that - we were just the ones that became the most famous because of

the way we decided to use the art world. We were creating billboards and

posters, which was very different from what everyone else was doing.

The way in which the

posters were made originally is very different from how the artworks were

created for the NYU show, since a majority of the content had to be digitally

recreated. So what is your attitude on that?

Is it the same, since the point was the message?

Yes. The creation,

how it's made, is actually unimportant to us.

All of us, I think, would say that we wish we were Gran Fury functioning

now, working digitally. It's a lot

easier now to do the work. It isn't as

labor intensive as it was before, and the work can be diffused a lot

faster. Now that you have Facebook and Flickr,

you can post things and get an audience of sometimes millions of people very

quickly.

So what role does a poster

serve now?

Avram has a lot to say about posters. I understand what he is talking about, and I

agree with him. A posters is effective -

posters for the street. I don't know how

effective they are anymore. We have had

this discussion. There was a time in the

late 80s early 90s when people did not have cell phones. Everybody walked down the street and was

looking around. Now when people are out,

they are lost in looking at their phones, so they are not interacting with the

street in the same way. So the visuals

you encounter in the street are not as impactful as they were back then. I think the poster has a relatively limited

use. I know Avram swears by them - - he

says that's the way to go. I think the

reality is to use the media that is relevant, and it's digital. We can do a piece and put it on Facebook and

it could be shared by a thousand people in five minutes.

One of the things that we want to do, and we have been

talking about this, is to put everything on some sort of website, since most of

the work was digitized for the show. We could then say to people, “Steal it! Take it!” The New York Public Library makes

it really difficult for people to access this information. That was not our purpose. The reason we why we gave it to the library

is that we thought people could freely access it, and that’s not what it is

turning out to be.

Do you have any

closing thoughts?

It is interesting. I find that the posters are unfortunately

still very, very sort of up-to-date, very present. I say, unfortunately, because 25 years into

the epidemic, we still are seeing some of the problems that were being

addressed when Gran Fury was working.

That feels a little frustrating, but hopefully, people will be able to

decide how to get it out there so everyone else can use it. I think the work remains alive, if you

will. It is vital, and that is a good

feeling, to know that the work isn't dated and it didn’t end up in the dust of

history.

I think the work is good.

I'm proud of the work we did. It

was really effective. It gave a face to something that had no face at the time. It gave a voice to people who were not able

to talk about what was happening. In

that respect, it was incredibly effective.

Something we were really proud of. We really were in the right place at

the right time, and we were the right group of people to do it. We're incredibly lucky and very fortunate.

Thanks so much to Robert for his generosity of time and stories!

Pictures of the interview courtesy of Joe Mondello; Women Don't Get AIDS bus stop poster via PublicArtFund.

Monday, April 8, 2013

Interview with Melitte Buchman

INTERVIEW WITH MELITTE BUCHMAN -

7 February 2013

Joe and I got the privilege of meeting with Melitte Buchman at NYU's Fales Library to speak about her part in the show, scanning some of the original posters and restoring them to look new. In addition to learning some of the more technical aspects of her work and the process, we spoke about larger concerns of digital restoration versus digital preservation, copyright and Cesare Brandi's treatise on restoration, which plays a large role in definition how archivists and historians operate today within their fields.

Here are a few sections from our conversation:

Could you give a general description of how you got involved in the process, who contacted you specifically - was it Edward or Hugh, or was it Michael Cohan?

It came to me through Edward Holland. He and I went to grad

school together. He's a panoramic

photographer, and he's with our staff here. They needed some high-res pictures

for the exhibit that they were putting out. So, I went over to them at the

gallery, and I said thank you for showing me the archival material. They were

too fragile to be through a scanner.

Anyway, I'm the digital content manager here, so it would've come

to me one way or the other. It's just came through a personal route. So when

people need things digitized for preservation, they talk to me because I'm part

of the preservation department and part of the Digital Library.

And how long have you worked here?

Nine years. Do you know

what a digital library is? Digital

libraries were initially invented because it was felt that students didn't want

to go to physical buildings anymore, that they wanted to go to the web and you

had to sort the truth out on the web as opposed to ‑‑ I can do this in

Photoshop and then make it look really neat. If you go through a trusted

portal, which NYU is, and you look one of our projects like this one,

you're going to see the truth of the object.

I think what we're actually talking about is what Cesare Brandi talked

about - the authenticity of the original artifact. Do you know Cesare

Brandi? It’s totally worth reading his stuff. It's about 45 pages. I don't

remember what it was from, but it was pretty revolutionary at the time. He was

talking about paintings and historical artifacts. The entire course of

preservation and restoration changed course with that treatise that he wrote

because he was talking about not making things nice, not putting the aesthetic of the present or the

materials of the present into ancient artifacts; so, the idea is that it's a

painting and everything has to be reversible. If it's something that needs to

be stabilized, then you need to respect the historical nature of the thing.

He's really the grandfather of that idea. I was saying that in digital

libraries we take that very seriously, so if we see something that's ripped and

dirty and all of that stuff, we don't try to make it better. We try sort of

this weird exercise where we're using really expensive high‑end equipment where

we could fix these things, but we know it's the wrong thing to do. When you see

a picture that we've made here, it looks within 1 or 2 percent, like the

original artifact, except for the fact that it's completely denatured. It's no

longer in the physical world. For example, part of the reason that we

photograph all of the physical pages with black around them, black surround, is

so you can see that it's a physical page. I find that's the biggest part of my

job is worrying about what is the end‑user going to need to know about the

context of this object to render it mentally correctly.

The thing with Gran Fury was that the posters were how old -

twenty years? And colors had shifted.

There was staining. There were broken edges. There were fingerprints. There

were all kinds of things, and I was about to do what I always do, which is

preserve exactly the look and feel of the historical nature of the thing. And

then I said, “This is what I am doing. Is this what is wanted.” They said, “No,

this isn’t what's wanted. What's really wanted is the way it looked back then.”

So, you get to go into Photoshop and change the white point and clean up the paper. Our equipment is really high end here, so the

result looked great. It looked new. It was huge, and we got rid of the moiré,

which is intrinsic to the printing.

(Referencing her computer screen) Here, this is the perfect

example. It's this kind of thing where if you're photographing something,

especially from a newspaper that has a core screen of about 80 or 85, that when

you digitize it at 300, 400, or 600, it adds this other patterning on top of it

that's not intrinsic to the original. There's a bunch of digital tricks that

you employ to get rid of it, so I did some of that with the Gran Fury things,

too. I don't know if you saw the installation, but it really looks

spectacular.

Yeah, that's what really inspired me to do this because it was

beautifully done.

My problem is it's the wrong thing to do. The only reason I did

it is because curatorial always stands on top of the service provider. I'm the

service provider but the gentlemen that I met ‑‑ it was only with their

approval that I would take this other approach. And part of that is sort of a

philosophical, anti‑colonial thing, like who are we to make decisions about

what your content is?

I have an example that may be helpful of this where we have in our

archives a collection called the Abraham Lincoln Brigade photos. The Abraham Lincoln Brigade was part of the Spaniard

Civil War era; communists go over to fight against Franco Luce, but they have a

core of photographers. Two-thirds of their negatives came to us and one‑third

went to Moscow. The two‑thirds that are ours are what photographers call “bulletproof”.

They're super, super dense, which really blows out the value. So it sort of

looks like a snowman in the snow. They look very high contrast and very light.

When I saw the collection, I knew that it was going to be a problem. We [had]

the negatives to process out, but the photographer was still alive, and his

name was Harry Randall. I did an interview, and I said, “You know, when you

were photographing this, how did you see this collection?” He said, “Oh,

they're supposed to look like a good, snappy black‑and‑white that you would see

in a newspaper.” I said, “That's not what they are. They're bulletproof negatives that are very

high contrast.” He said, “You know, we never knew where our chemistry was

coming from. We would be developing a stream in the middle of the night, trying

to avoid dying. What we did was we overdeveloped everything with the hope of

getting anything,” which means, first of all, he's an amateur photographer.

That's not how you handle that. But second of all, it allowed me the

flexibility of being able to say since he is the creator and he is telling me

what he thinks this thing can look like ‑ should look like - then I can take my

digital tools and make it so. I didn't make it so in the master file. I made it

so in the file that we called the derivative making file. So, the master file

actually is a 16‑bit negative of an incredibly low contrast. But the D file, which is what you would see

small JPEGs minted from on the web, looks as close as I could get to a good,

snappy black and white because that's what he had asked me for. That's how he

had defined the collection himself.

So normally I would never, ever do this. I want to make this

really clear - it's bad archival practice to go in there mucking about and

making decisions about bettering something; it was only because the curator

said, “I am Gran Fury, and this is the way I see it” that it let me do that. One

should never be doing that normally.

You provide an answer that I was partially expecting. But, for

example, I spoke with two Gran Fury members, and they each had a different

attitude toward it. Originally as a collective, they had said, you know, “The

art isn't the point. The posters aren't the point. They're not meant to last. It's the message

that's the point.”

Okay, you have to read Cesare Brandi now because what the

collective is doing, they’re making a new object. They’re not making the same

object. In other words, if somebody else did that, it would be infringing on

copyright. Because they have their own copyright, they may do it because it's

their intellectual property. But Cesare Brandi also talks about the fact that

if you are doing a restoration or preservation, you can never have the artist

involved because the artist will always remake the object.

Gran Fury, from my point of view, sees their pieces as content,

and if they're not content, they are content and container. And with content

and container, they have sort of a unique balance. Here we call that kind of

thing “essence and wrapper” - you have the essential message, but it’s mitigated

by what the wrapper is. So, if you see a letter written by George Washington

and the paper is faded, that tells you a great deal not only about the content,

but about all these other sort of characteristics. The object is old, you know.

It's been around a long time. It should be venerated, whereas if it's on a

pristine white sheet of paper, it's no longer the thing, itself. I think people

who are creators or artists tend not to see that, and people who are archivists

and historians tend to see that.

***

You can't talk about digital without talking about copyright, and

we are not able to serve up many things after 1924 because of the copyright

legislation that was passed. You know the story: Ronald Reagan was president,

Mickey Mouse was about to fall out of copyright, and Disney wooed Congress in this

huge, gross political move.

Copyright went from something that was meant to protect the

creators so that they could gain some income from it. And it became something

that corporatized the assets, themselves. And the irony, of course, is that

nobody cared that much about Mickey Mouse, but it forever changed the landscape

of copyright. So that, for us, is always the painful thing. Do we put this

material out here in spite of the fact that we might get sued or we will have a

cease and desist sent to us or don’t we? We've had to set up very distinct user

classes about where these digital files can be seen.

Right. So, to rehash, digitization does change the nature of

the object. Copyright plays a humongous issue.

Putting [archival materials] on the web is seen as publishing,

so it falls under publishing laws, as well. There are always generational

issues in the past. If you had a book and you wanted to save it in

microfilm ‑‑ Microfilm is less desirable than the original book. The thing with the digital copy is if you

make a copy of a digital copy, it's exactly the same as the digital copy; so,

the potential goodness of the file can be exactly the same as the original. And for some reason that has turned against

us in a bad way, when we had hoped it would be liberating. I think in some ways

it is liberating because you can now go to the web and look at, you know ‑‑

Digital Scriptorium will show you the most valuable manuscripts held in this

country, which you never would have been able to see except by getting a pass

from NYPL and gloves and all that. So there's some very good things about being

able to digitize.

***

Going back to earlier in our conversation, I love that term you

use[d], ‘denaturing’. I really like that. I think that gets to the heart of

it.

It's kind of a weird Zen exercise in a way. There are a lot of

digital tools that are made specifically to enhance and make things look

better. We actually have to turn all of those tools off. We calibrate our

equipment so that what you see is what you get. That's hard. All of our

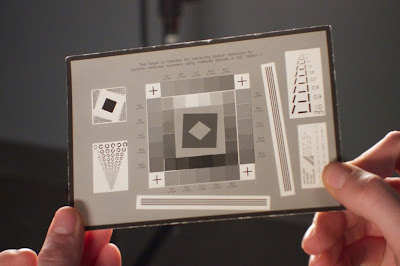

scanners we have to use the photo spectrometer made by X‑Rite. And what we have to do is we have to

calibrate and characterize so that what you see is actually what was

there. It doesn't make it brighter. It doesn't

make it redder. It doesn't make it bluer. The photo spectrometer that we use,

which is a good one, is an expensive device, and you have to be trained on

it. So, you know, we use sort of a moderate

level of spectrometer, which is about $3,000, but people like L.L. Bean, who don't

want to get 10,000 shirt returns because it wasn't exactly that color

blue, use the really high‑end. You could pay millions of dollars. They're not

making any of the stuff for us. We're sort of backing on to ‑‑ We're

appropriating other people's technologies to manage our own.

In my defense, I really enjoyed changing the poster to make it

look cool, and I really enjoyed using my digital skills to make it look big and

sharp and detailed, but it's a bit of a fabrication.

Thanks to Melitte and the Fales Library staff for being so accommodating.

*Photos courtesy of Joe Mondello; portrait of Cesare Brandi via Cesare Brandi official website.

Wednesday, April 3, 2013

INTERVIEW WITH MICHAEL COHEN -

7 February 2013

Being able to interview Michael, who helped foster discussion and curated the show, was incredibly helpful in understanding how the show was realized. Here are a few portions from the interview - truthfully, I had a hard time choosing sections to post since the entire interview intimately narrates not only the workings of the show, but presents thoughtful insights into the future of activist art and the consequences of "institutionalized" work of this nature. Hopefully the thoughts here will help to spark a larger dialogue around the preciosity of art objects, our obsession with the 'authentic original' and why we need to address activism in 2013.

If we could start out with your interest in Gran Fury and how the show came to be…

Sure. I had contacted Marlene McCarty about doing a solo show at the gallery, and I was doing [this] pretty far in advance because I knew it would take a long time to do Marlene’s project; so right when I got hired at 80wse, I contacted her. As we were developing her show, she brought up the idea of, “Well, should any of the Gran Fury work be part of the show?”

Oh, okay.

And so I met with Gran Fury about that, and there were some vague talk about maybe doing a Windows show because we have these two satellite spaces. Basically, their position was they did not want to have any type of Gran Fury retrospective or survey or anything.

I had some awareness of their work, but in many ways, it was blurred by time, and I took it upon myself to really familiarize myself with their work, and did a lot of research. And the more I got to know them, I thought, “Huh, this is really important work that’s never had a survey before,” and I started feeling that it was really a disservice to their ouevre to have it be a small adjunct to Marlene’s show for several reasons; one, I thought it was more interesting as a body of work than to have their projects be a sideline to her show; secondly, there’s not a million Gran Fury pieces, so I felt to some degree that if we showed half of Gran Fury’s work in a Windows show, it’s going to be very hard for them to have a survey exhibition in New York City in the future, if we did that. So then, the next time I met with Gran Fury, as far as I remember it, I came with a proposition of a full show. And they were dead set against it because they were very resistant to the idea of “the institution” – the institutionalization of their work; but, I had had a lot of time to think about why it would be worth doing and eventually was able to win them over to this point of view.

So, you were obviously very good.

You know, I thought of what arguments would be convincing to them and sort of wore them down, in a friendly way, through logic and persistence. Initially,they were like, “If we have a show at MoMA or some other major art institution, what’s that going to mean for the artwork, which is meant to be produced in an anti-institutional context?” So, what I said to them was, “Okay – first of all, this isn’t an art institution; it’s an adjunct of an educational institution.” I emphasized the educational context, which wouldn’t be possible at most other institutions in the tri-state area, and brought up the idea of doing a workshop where students could learn “The Gran Fury methodology” and work with them. I was like, “You know, none of us are getting any younger. Don’t you think it would be interesting to re-expose a younger generation to your work and maybe work with them so they could learn what you were thinking about, and maybe they could make work utilizing what they learned about your approach?” And in some ways, they were more excited at that possibility than of actually having the retrospective (laughs). But, the show and the workshop went together. And the other thing I said to them was,

"In most other institutions, you and the curator would have a fixed role, but what I picture for this is you turn the mediation of the curation into an artwork, itself, and actually make your own history and contextualize it. I’ll work with you on that, but you’ll have the most say over how your work is historicized, which is going to happen at some point anyway. Why not work with me on that so you have the most voice in that process?"

And that was very exciting to them, as well, on a conceptual level. So those two points were important in our reaching an agreement to do the Gran Fury survey.

I heard that some of the images were adhesive [vinyls]. Why did you choose to use this material instead of another material that could have been re-used?

We did think about that, and that was actually my suggestion. I had a lot of concerns about whether adhesives would hold and whether it would start to bubble, and because we had pretty tight deadlines in terms of installing the show, I was concerned. If we spend a couple thousand dollars on a stick-on and it doesn’t work, what are we going to do? Because in that case, we may not have the time or the funds to redo the piece, which would be a huge disaster. But their point, which I came around to, was that the pieces had originally been attached to surfaces - they were glued onto the wall in their original format, and a billboard format was not as true to the original process of the piece as sticking it on the wall.

That makes sense.

I felt like if we could do it, I wanted to do it to be as true to the concept of the piece as possible. So we ended up doing endless format tests of different types of paper and attaching it ourselves, versus having a peel-off. We’d leave them up on the wall and see, does it stick? It didn’t. Ultimately, we ended up with the format we did based on the fact that it didn’t fall over and didn’t bubble up too much.

Let’s go into that - that the pieces were meant to be more temporal. And you just said that they’re not the real pieces, so I want to talk a little bit more about that.

I meant the original. They’re real.

Sorry, that’s what I meant.

They’re not the same as the original really was, I should more accurately say.

So, you feel the nature of the piece has changed, now that it has been digitized? Do you see a difference in the essence of the piece?

Not necessarily the message, but because it was made a certain way originally and then it was re-created, most of the time from a high-res scan.

Can you speak to that? How you feel about the nature of that changing?

Yeah. I think Gran Fury wasn’t ever excited about having a set of originals that would be archived or presented in a museum as the original piece, and generally, they didn’t have any of the originals in the show, as you must know from interviewing everybody. I think to them, in a Walter Benjamin “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” kind of sense, it was more interesting to present works that were not the originals and generally not have originals that could be some sort of valuable masterpiece as part of the group’s work. Conceptually, I think it [made] much more sense to have a piece that said, “I’m a reproduction and made specifically for this new context using a lot of ideas from the original piece”, but also saying, “I’m addressing my re-contextualization”, in terms of addressing their audience in their work and their antipathy toward commodification.

What do you think the physical role of the Gran Fury poster is going to be in the future? And second, what you do foresee activist art looking like?

I’m not sure. I think it’s going physically into new directions, because in terms of the future of what you’re calling original Gran Fury works, there is a plan to do high-res digital scans of all of their work and put them online as freeware. I think one of the most important contributions of this exhibition, in the future, won’t be the show, itself, but that we got those guys together to either scan originals or make versions that could be turned into them because those scans that we made are actually the basis for this free library of their work that’s going to happen at some point.

Conversely, my understanding is that several major institutions like MoMA are talking about buying whatever part of the archive the public library doesn’t have, so there may be ephemera or originals that do end up becoming part of the institution.

As far as the future of activism, it’s not my main area of expertise.

I wasn’t looking for an “official” answer coming from an area that you’re enmeshed in; just your thoughts after working with this and seeing the chemistry they had and talking about art from the 80s. I think the message is still pertinent, which is sad, but true when you’re looking at these AIDS statistics and the topic in general, that AIDS still exists. And unfortunately, some of the stereotypes and falsities are still coming around. Maybe not so much in New York City, but certainly elsewhere.

It’s kind of a complex question that you’re bringing up. I think the educational panels we had, in a way, were as important as the show, itself. Again, the dialogue was so important. One of the more interesting ones…we had a panel where AIDS activists from the present and also back from the 80s, healthcare activists and couple of members of Gran Fury got together at the Gay and Lesbian Center and we had a panel on the past and future of healthcare activism and what role art could have to that. An important aspect of that panel was to address your question. However, in the end the panelists didn’t resolve the question – everybody felt like a lot of advances had been made in healthcare that’s available to people suffering from AIDS and that the healthcare activism in the Gran Fury posters, making people aware of them, did have a major impact on that issue. But then, what also came up was that there’s become a type of class thing where the number of more educated and often more white people who could be at risk of getting infected is shrinking; but with minority groups and the lower class, which I wasn’t aware of, the numbers [are] increasing or going back to older infection rates. This is also a problem in certain third world countries. There was a feeling that there was a role for art in making people aware of this. And a lot of the students weren’t aware of these dynamics, so I think what a lot of the young artists and the people who came to the show learned was:

A: I think they haven’t been as aware of the original crisis, and

B: Maybe some awareness was raised that it’d be interesting for artists to explore the continued fight over bringing equity to lowering infection rates. And getting art involved with women’s reproductive rights, which is another pressing issue.

So, when the students were working with Gran Fury, they got involved in making posters addressing both those issues. I don’t know if numerous people are working with those issues, but I certainly think both reproductive rights and rising infection rates might be interesting for artists to get involved on an activist related level: making graphic designs or giveaways or online projects that could raise awareness of those issues.

So, you think the poster is still a viable, effective medium in 2013?

Yeah.

Thanks to Michael Cohen for helping make this project possible and for his insight.

*Images that do not depict the interview via: itcctiVirginiaedu, Vimeo

Saturday, March 16, 2013

INTERVIEW WITH EDWARD HOLLAND AND JOE MONDELLO -

17 December 2012

After a bit of a hiatus, here are some snippets from my conversation with Edward Holland, former registrar at NYU Steinhardt Gallery, and my friend, Joe. Edward was kind enough to offer his apartment for the afternoon, where we were able to discuss the specifics of preparing the Gran Fury exhibition. Edward offered very unique insight, as he not only worked closely with members of the collective, but also got to experience how the show was received by members of Gran Fury, ACT UP veterans and visitors to the show that were being exposed to the AIDS crisis for the first time.

What was your first exposure to Gran Fury, and did you have

any initial impressions?

I had no idea about them before I started working on the

show at NYU, and as I found out more, then I remembered seeing certain pieces.

I mean, I was young at the time of the AIDS crisis, but I wasn’t unaware. So, I

was 10 years old in 1990, which sounds really young. (To Joe) And you can roll your eyes…

Joe Mondello: No,

I’m glad ‘cause that would mean you would have seen the bus posters.

Exactly. I was old enough to remember seeing these images

and hearing these facts, hearing these stories. Later when I was trying to

think about it, I was really impressed [that] my school at that time was so

actively involved in sex education and AIDS awareness. I mean, we had classes

on it. We talked about it all the time in our current events class. When I

looked back on it, I thought, oh wow. That seems very progressive for a

suburban public school.

Yeah, no kidding.

But initially, I didn’t know who they were until I

started working on the show and really getting involved. I was interested to

know more about this. How are we going to translate this into an exhibition?

That was my first question. The good news is it wasn’t up to me to answer that

(laughs). But the more I read, the more I got involved. It’s a different

generation – I think that that’s another thing about this show that I found to

be really interesting, the stark generation divide between all the different

viewer levels.

Could you describe your initial meetings with Michael and

the collective?

It was a bit intense because I’d never met them. [I was]

still learning about what they did, who they were, but I really had no idea

about them personally. I had no idea how many there are, what they [were] going

to be like. We sat in one of the rooms in the gallery, and it was me, Michael,

Hugh, Tom, Marlene, and John, I think.[i]

And I had met Marlene because we had done a show of hers previously, but I’d

never met the other[s]. It was just head-spinning because once you get them in

a room, even just three of them, and get them talking, they just boom-boom-boom-boom…back

and forth. It’s really hard to get a word in and it’s difficult to keep them on

track because all of a sudden, they’re just riffing off one another and going

somewhere else. So, the first meeting was very intense. It gave me vertigo, but

it was a good meeting. And it was a very good introduction to [what] the

process [would] be [like] because there was a little bit of a mania, a time

crunch and so many moving parts. All the copy that goes into something has to

be vetted by everyone else in Gran Fury. And all the images need to be vetted

by everybody else. There was this weird, idiosyncratic bureaucracy that we had

to deal with within their group, but NYU’s [also] a huge bureaucracy, so we had

to deal with it within our own side, [as well].

So, how much prep time were you given to make those

decisions? How many weeks, how many months –

Well, the show opened the end of January, and Michael had

been working on it for much longer, obviously. I started working on it probably

around the beginning of 2011. So we had about a year to do everything, but you

need at least a year to plan a show like this. When I say we started planning,

we just started thinking about it. We really didn’t ramp everything up until

well on into the spring and the summer of 2011. So, about six months before the

show opened is when we were really starting to kick it into gear. Those first

four or five months were really sort of lining ducks up, reaching out to

people, saying, “Hey, do you have this? Where is this? Do we have access to

this?” Very cursory, preliminary things. And you need lead time for the

printing and everything. Line up the contractors and samples of everything. Once

we were getting really involved, it just sort of took on a life of its own.

[i]

Michael Cohen (curator), Hugh O’Rourke (preparator), Tom Kalin, Marlene

McCarty, John Lindell (Gran Fury members)

***

So, going into the tone of the show, how important it was

for them that you [all] brought in that historical context, [arguing] that

these pieces couldn’t be presented in a vacuum. I think it was so important

that you put it into context, through the didactics and other pop culture

references. Could you speak to that a little bit?

I know that they had a really hard time with that because

so much of their work is so specific. You know, it’s large city, late 80s,

early 90s – and that’s a very particular viewership that they were catering to.

So then to create an institutional survey of this work, but still make it

relevant – they had a really hard time trying to parcel how that [was] to be

done. And their solution was to put up as many relevant visual keys as possible:

attorney general shots and pop culture references and global culture references

and facts and figures and all of those things to condition the viewer to

understand what they were looking at. And that was all them. It took them a

long time to get there, but I thought their solution was very elegant. Having

the little placards with all the text to explain a grouping of images I thought

was a nice touch. I know they fought a lot about that copy because they’re a

collective. Everyone had a different idea as to how this needs to be presented:

“It needs to have more facts.”

“It needs to have more emotion.”

Everyone has a different stake in it, and what they ended up

with was their answer. I can’t find any faults in it because everything made

sense, and so much of it, at a certain point, was ad hoc. For [example, in] The

Pope and Penis room, that inverted cross [was something] they had decided

to do at midnight on the Friday before the show opened. They were working, [and]

they didn’t know how the arrangement would go.

“Oh, what about an inverted cross?”

“Oh, ha ha.”

And it worked, it stuck.

Avram has a wonderful collection of original ACT UP flyers

and posters and all the stuff that when

you would go to ACT UP meetings – there would be a long folding table that

would be just piled high with stacks of different flyers about events and protests

and things, and you would pass it on your way in and way out. And originally,

they were thinking they would set up a table like that in the gallery to sort

of give you an idea as to this is what it was like – to have all this

information and have it handy, have it out. At a certain point, that idea got

scratched, and I can’t tell you why, but then the idea was, “It’s so important

to have that, let’s put it on the wall.” And it became an idea to paste one

wall with nothing but these handouts so people understand what [they] were up

to, what was so important visually with these sort of Xeroxed handbills. There

were a lot more takeaways originally. They wanted to have a lot of pieces for

you to take with you when you left.

They had The New

York Crimes…

There was New York

Crimes, there was Four Questions.

There were postcards and other posters. There was the kiss-in poster[i],

the lesbian couple for Kissing Doesn’t Kill

as a postcard, and the Wall Street money.

So, about five. I think at a certain point, maybe aesthetically, they didn’t

want to have a folding table in the middle of one of the rooms.

I’m trying to remember. Were the stickers…

Oh, the stickers. So six [takeaways].

Yeah. The stickers were on the windowsill in the first

gallery as you walk in, correct?

You would walk in and on that windowsill were the kiss-in

poster, the additional copies of New York

Crimes, the postcards, and that’s it. And then in Gallery Four, there was

the tableau of Four Questions. And

then in Gallery 5, at the time, because the gallery’s different now, there was

a clear acrylic placard coming off the wall and there was a stack of stickers

on there.

So going to the construction of the galleries… I don’t

know the numbers of the galleries, but the fact that [the space]was split into

four – and how incredibly inconvenient that was…

It was really inconvenient, and curatorially, it made for

challenges, but when you rise to meet those challenges, it makes for a great

installation. And I think one of their solutions was to paint walls different

colors in different rooms. Thinking back on it now, in Gallery 5, where the Men Use Condoms or Beat It stickers

were, they painted one facing wall a very distinct purple and adjacent to it

was Women Don’t Get AIDS, which is

predominantly purple and having that color interplay all of a sudden created a

completely separate space. That room really felt as if it was a completely

different room than anything else because of the purple. And on the purple wall

were the Control pieces[ii]

blown up very large. So that room felt completely different than the rooms next

to it, even though they were the same size. That was a decision they had made,

and they had done their research, really thought about everything: all the

different colors, where the colors were going to go. All these decisions that

they labored over, and I’m sure they fought over, were so dead on. As I said

before, the show was top-notch.

[i] Read My Lips (male version), 1988

[ii] “Control.”

Artforum, October 1989

***

What was the most rewarding part of this experience for you?

I’m going to get all misty-eyed. It was when people who

were in New York at that time, dealing with these things, came through the show

and immediately had a reaction. I mean, the opening was unbelievable – this

bizarre ACT UP class reunion, people coming out of the woodwork and talking

with one another. There was a definitive…not sadness, but heaviness about the

atmosphere. But it was still celebratory.

“I’m so glad we’re all here. I’m so glad this work is here. I wish

so-and-so could have seen it.” And I think having people have a reaction like

that is very rare, and it was amazing to me to watch that happen over and over.

One [reaction] that really was awesome was when Tom Kalin saw Riot for the first time. That was

awesome because he loved Mark, they were roommates, and he couldn’t get over

that this piece still existed – that it was still on the wall. It was these

little moments that I thought were so fantastic.

I work in an art gallery, and I deal with art; but it

changed the role of the gallery for a little bit, so it was no longer

presenting art. It was presenting something more, and that interaction was

happening every day… I mean, so many people saw that show and everyone came

through and said, “Thank you. What a great show. Where’s this going to go next?

What can I do?” It was just so much for so many people. That was the most

rewarding part. Very rarely do you get to work on something like that. I had no

relation to Gran Fury; I had no practical relationship with them outside of

this show. It was their show, but peripherally, I got to be included. Give me a

break, what a great experience! Hopefully they were pleased. When you talk to

them, you’ll find out. I hope so.

I’m sure.

I wonder what will happen. Hopefully, they’ll travel the

show and go somewhere else. And I would love to see it there and see what

happens.

Thanks to Edward for being so gracious with his time and sharing his experiences.

*Images via HyperAllergic, DailyServing, Blogspot

**Original photos courtesy of Joe Mondello

Wednesday, February 13, 2013

Interview with Hugh O'Rourke and Joe Mondello -

14 December 2012

My first interview was with Hugh O'Rourke, preparator at NYU Steinhardt Gallery, which hosted the Gran Fury show. Hugh was instrumental in setting up the gallery space and helping to digitally re-create art objects, including The New York Crimes. My friend, Joe Mondello, an artistic photographer and former activist artist during the AIDS crisis, was gracious enough to come with me, take a few pictures and contribute first-hand knowledge. Below are some quips from our interview:

Did you make a bid to

Gran Fury to have this show here, or how did it come to this space?

Michael [Cohen] deserves a lot of credit in the preliminary

aspects of getting that all set up and once the show was scheduled and the

budget was approved, then Gran Fury took over. Michael really made a case for

having the show and having the budget that it had and all those type of aspects

before it was solidified, and then once it was known that they had the slot and

they were going to be here, then Gran Fury really took over with the planning

of the show.

He was the one who

told me that most of the content was digitally recreated, which is one of the

huge things that I find fascinating.

They all had kind of

a specific specialty or role – I found that interesting because they’re working

as a collective and it’s under Gran Fury, but the way in which they specialized

and broke up the tasks is very interesting.

If I remember correctly, John Lindell also did most of the

printing onto the adhesive paper, so there was also very detailed things going

on like what kind of adhesive goes on the back of these wall decals. We put a

bunch of those decals up and then a few of them fell off the wall within a few

days, so then they had to be reprinted on a stronger adhesive, but John really

took that over, where in other cases for other shows, I would do that. They

were very hands-on, doing the printing themselves, and I feel like in a way

that harkens back to their original practice because they were doing everything

themselves. I think they wanted to keep that going, but it’s also interesting

to note that almost the entire show is gone because all that stuff was just for

the show and there’s no way to save any of the vinyls or the wall adhesives

because the only way to get them off the wall was to basically destroy them.

I didn’t know that

about the vinyls.

If the show was to travel then everything would have been

reprinted anyway. So very few things, except for the Riot painting and Control, which were in the back of the gallery, those were the original

pieces, but I would say almost 80% of the show was created from digital files

printed and at the end of the show was destroyed. It was all basically for

one-time use. Which is interesting, I think.

Yes. So, when you’re

talking about working from the digital files, did they just have scans or did

they have to recreate? I know that Edward mentioned that for the handout of The New York Crimes, they took the new format of The New York Times. Why did

they do that? Why didn't they just go back to the original format?

That’s an interesting question. The reason – a lot of things

when you’re doing any sort of production end up being for very logical reasons.

So the reason for that was that the new New York Times is a different format,

so if we were sticking new papers into those – if we would have went with the

old format, the paper would have been too big, because the old New York Times

was a smaller version and now the new version had to match. There was no other

way of getting around it because no one saved the old newspapers.

So [to print] the

papers and the stickers, Men Use Condoms Or Beat It, did you go through the

Albany studio as well or was that local?

That was done locally. We had a color test done. There was a

proof – with everything, there [were] proofs, so we could check and make sure

they were as exact as they could possibly be, and then we printed the stickers

locally. I was going to say I think another interesting story would be to talk

to Melitte Buchmann because some of the things were too big, and she actually

ended up taking a high res photograph of one of the pieces. I think that was

the Kissing Doesn’t Kill poster, so that, the vinyl, large blown-up version

was actually taken from a photo and not even from a scan, if I’m remembering

correctly. She was someone that Ted and I had both known, and she works at NYU,

too. So you start all these avenues that you know – you trust people.

***

Do you think the

pieces remain relevant today, and how so? Obviously, I’m coming in with an idea

that they do, but I would like to know your opinion.

I think something like Kissing Doesn’t Kill is an

interesting one because I think they had a very instrumental role with that

piece, specifically, because thru learning about the show, that piece seemed

like it was one of their most visible and successful and thought-provoking

pieces. I think when AIDS was in its infancy, people didn’t know the details of

how it was contracted, and I think people didn’t realize that kissing and

saliva contact wasn’t a way transfer. So I would say that that piece was their

most successful as a historical piece. But then I think even the large baby

[Welcome to America] – I feel that really held up. I think they said now South

Africa does have health care, so we’re still the only country that doesn’t have

[government-provided] health care. I think when you put something in that

context on a billboard-sized piece, you really have to recognize.

A call to reality.

Yeah, a call to reality. Or sometimes people in America,

because America’s so large, start to lose perspective on what the rest of the

world does.

Absolutely.

Sometimes just putting it in a sentence like that helps

people realize in a lot of ways, a lot of the rest of the world has moved on

and developed ways to address health issues that America either ignores or

chooses not to follow.

Working with the

group, obviously you got a lot of anecdotal information, or did you?

Yeah; hearing about the controversy in the Venice Biennale –

the piece was held at customs. And then seeing some of the other materials,

like the graffitied (sic.) piece, Kissing Doesn’t Kill in Chicago. I think it

just gives you a really broad understanding of the time period and how people

felt about this imagery. It gives it a little context.

I think also the

nature of the imagery behind the images, if that makes any sense [is

important]. For example, the reason there are three female versions of Read My

Lips is because those lesbians in ACT UP felt they weren’t being properly

represented and that it wasn’t equivalent [to the male version]. And the male Read My Lips [image] is a porno shot from San Francisco. I think that’s

hysterical.

I think also just being at the opening and seeing a lot of

the group who [were] still alive show up and seeing the community that was

created through making all these pieces – and then realizing that a lot of

these people who were in these pieces have died. So, seeing people come

together and celebrate what was done and remembering people that weren’t here.

Absolutely. Did they

bring up Mark Simpson?

They brought up Mark Simpson and talked about him a few

times. He was featured in some of the didactic material.

Joe Mondello: I was

just curious. You said you were 8 or 9 when the Magic Johnson thing happened.

Are you about 28?

I’m 31.

Joe Mondello: I’m just

trying to place you in my own historical context. But I’m just curious as to –

Karen said the other day that she’s not sure that she’s met anybody with HIV.

Do you know of people who’ve died of AIDS or have HIV?

To be honest, no.

Joe Mondello: How

different a world it is. When HIV hit, it didn’t have that name, but it was

1981 and I was 30. And it was like what? A cancer that only strikes gay people?

That’s pretty interesting. And then years went by and it just got worse. It’s

very strange. Imagine something like that happening now – just some weird

disease coming out of nowhere and all of sudden people are wasting away and

dying in six months.

Traumatic, too.

Hugh provided great detail about how the exhibition was designed and the detail with which the space was engineered, factors which the collective couldn't control originally, since the posters were posted in open, public spaces.

As far as the digitization of the posters and the implications this holds, Hugh argued that the magnification of some of the pieces and their re-creation served the space and public education/experience:

Thinking about it, that

[the posters] were made in an obviously very different way in the 80s, early

90s, and the way they were remade, what implication, if any, do you think that

has?

For me, it starts with a grassroots effort and the physical

nature of either replacing a newspaper with your own cover page or putting up

posters around town (wheat-pasting). And then once it gets to the art gallery –

you know, these things are historicized, but they’re also blown up. I feel like

they’re synonymous. One, you’re putting the pieces in a widespread manner and

then here, you’re in a gallery and it’s very focused, so the pieces are blown

up to a larger size. But both have this kind of awareness factor – we have a

lot of windows, so people could see in, and for people to see in and recognize

what those things were, they had to be blown up. So to address the public, I

think that’s one of the reasons to blow these up, so they can see them out of

the corner of their eye. They don’t even have to come into the art gallery.

They can look through the window and read the text – and that’s part of the

kind of advertising component that these things had. They were super readable

and catchy, in a way. So, instead of having hundreds of small posters, they’re

almost being combined into one giant [piece].

So, there’s kind of a

balance?

Yeah, to me, there seems like there’s a balance. I think the

idea was to blow them up to have the same impact that they would have had.

In this case, he feels, the high-quality replication of both the posters and art objects served to provide pieces that were incredibly similar, if not identical, to the originals.

*Thanks again to Hugh and Joe for their generosity of time and openness in conversation.**Photographs of Gran Fury pieces courtesy of cyborgyoryie, NYTimes

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)